Emergency Physicians Respond to Flooding in Kerala

By Dr. Sonia Haris, Dr. Venugopalan Poovattuparambil, Dr. Naveen Anaswara & Dr. Kevin Davey

Operation Navajeevan

In August, 2018 India’s southern state of Kerala experienced its worst flood in over a century[1]. Over a period of weeks, heavy rains, rising flood waters, and land slides left an estimate 483 dead and hundreds of thousands displaced[2,3]. In response to the devastation, the National Health Mission, the district administration & ANGELS (Active Network Group of Emergency Life Savers) initiated ‘Operation Navajeevan,’ a joint private-public partnership with healthcare facilities & NGOs in the region to provide medical relief to flood victims. This article describes the relief efforts in Kozhikode, a costal region of Kerala, where operation Navajeevan was initiated.

Lines for medical care at one of the relief camps.

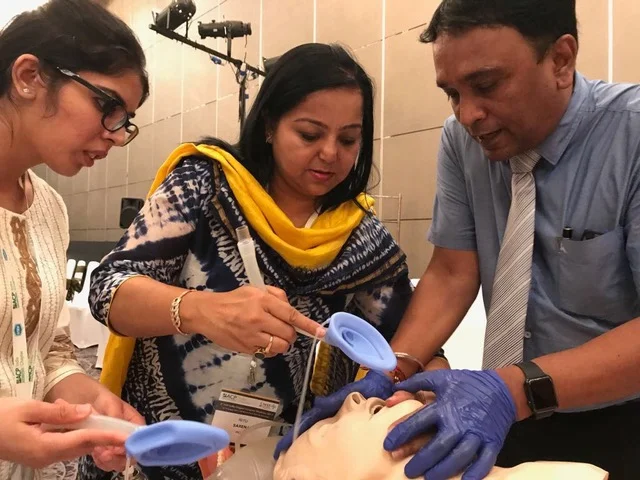

Over the past several years, hospitals in Kerala have increasingly invested in strengthening training in Emergency Medicine. Kerala has an estimated 20 Emergency Medicine residency training programs, supported through various pathways including government sponsored MD and DNB programs, as well as Masters in Emergency Medicine (MEM) programs working in partnership with either the Society for Emergency Medicine in India (SEMI) or George Washington University[4-7]. The effect on the overall healthcare system has been an increase in resilience and an improved ability to respond in times of crisis.

Emergency Providers tending to a patient in one of the relief camps.

Despite little formal training in disaster relief, the physicians running the day-to-day operations of Operation Navajeevan created a highly coordinated system to provide care for flood victims. Medical teams consisting of a Chief Medical Officer, a local health inspector, a team of physicians, and volunteer Emergency Medical Care Technicians (EMCT’s), as well as local volunteers, were formed in each relief camp to ensure 24-hour medical services for flood victims. The district was divided into 7 zones and high-level tertiary care centers, both public and private, were identified in each zone. Critically ill patients presenting to relief camps were transferred to the nearest higher level facility in their zone. During this time, private hospitals agreed to provide free treatment to all patents presenting from the flood zone. A command center was established at the district medical office to supervise and coordinate logistics between camps. Medical Officers from each camp sent daily briefings to the command center detailing the number of patients, types of cases being seen, as well any logistical difficulties. Five mobile ICUs and 40 ambulances under the supervision of the Active Network Group of Emergency Lifesavers (ANGELS) were kept on standby throughout the district to respond to emergencies and provide additional surge capacity. A mobile medical record was created to document the cases seen in each camp.

Physicians and Paramedics from the George Washington University Masters in Emergency Medicine program from Aster MIMS Hospital Calicut.

During the operation, 280 medical relief camps were set up across Kozhikhode. In the 14 days that the camps were open, more than 40,000 flood victims were treated by local emergency physicians, residents, nurses and paramedics. The most common reason for presentation to the camps was for exacerbation or ongoing treatment of chronic medical conditions (18,490 or 46.3% of all cases), such as hypertension, congestive heart failure, diabetes, and renal disease. As patients were unable to obtain access to their regular medications during the flood, many went unmedicated, which resulted in severe exacerbations of their underlying illness. This represents a drastic shift from prior floods elsewhere in India where infectious diseases like acute respiratory infections and gastroenteritis had been the most common ailments affecting camp attendees8,9. Also unique to the relief efforts of Operation Navajeevan was a focus on the treatment of mental health. Over 5300 patients, roughly 12.5% of all cases, presented to the camps for treatment of mental health conditions, most commonly depression and PTSD. Half of these patients had pre-existing psychiatric diagnoses, and their primary medical need was resumption of their regular medications, most of whom had lost access to them during the flood. In order to combat the strain on these patients, psychiatrists and clinical psychologists were made available at the relief camps to offer counseling and support. To our knowledge, this was the first such effort to provide treatment for mental illness during a natural disaster in India. Along with providing direct medical care, camps partnered with local NGO’s to provide public health education sessions which included training on personal hygiene, wound care, and clean water sources. Classes were also held on prevention of and first aid for snake bites, control of vector borne diseases, and avoidance of electrical injuries in flood affected areas. Operation Navajeevan represents one of the first successful private-public partnership models to be utilized in disaster relief in India. The centrally coordinated approach allowed for judicious use of resources and helped avoid duplication of services. Additionally, Operation Navajeevan was the first flood relief effort in India to perform mental health surveillance and provide mental health services in the camps. The model used in Kozhikode was so successful that it was later replicated across the rest of Kerala.

Authors

Sonia Haris is a 3rd year resident in Emergency Medicine enrolled in the Masters in Emergency Medicine training program at Aster MIMS Calicut. She completed medical school at Calicut Medical College, Kerala in 2003 before going on to complete a surgery residency at Sharjah Kuwait Hospital in the United Arab Emirates. She received her Medical Royal College of Surgeons certification in 2008. She worked as a surgeon before joining the Aster MIMS Calicut Masters in Emergency Medicine class in 2016.

Venugopal Poovattuparambil is the Director of Emergency Medicine for DM Healthcare. He is also the Emergency Medicine residency program director at Aster MIMS Calicut.

Naveen Anaswara is the District Programme Manager for the National Health Mission in Kozikode.

Kevin Davey, MD is an Assistant Professor, Emergency Medicine at Ronald Regan Institute of Emergency Medicine, International Division George Washington University

Sources:

1) Baynes, Chris. Worst floods in nearly a century kill 44 in India's Kerala state amid torrential monsoon rains. The Independent. Aug 15,2018.

2) Death toll in Kerala floods rises to 417, 36 people still missing. India Today, New Delhi. Aug 24, 2018.

3) National Disaster Management Authority. On Twitter. Retrieved April 11, 2019.

4) Indicative Seat Matrix - DNB PDCET (Post Diploma) Centralized Counseling July 2017 Admission Session. https://www.natboard.edu.in/pdoof/cns17/emerg%20medicin/DNB%20PDCET(Emergency%20Medicine)%20Indicative%20Seat%20Matrix%20July%202017%20-%2006.09.2017.pdf. Accessed April 11, 2019.

5) Articles: MD Emergency Medicine (MCI Recognised).” EmergencyMedicine.in, Medical Council of India, Oct. 2014, www.emergencymedicine.in/current/articles.php?article_id=56. Accessed April 11, 2019. EMERGENCY MEDICINE 5

6) SEMI - 3 Year Masters in Emergency Medicine.” President Message - Society of Emergency Medicine India, Society for Emergency Medicine India, www.emergencymedicine.in/semi/semi_mem_centers.htm.. Accessed April 11, 2019.

7) Educational Partnership Programs in India.” Partner Institutions | The Ronald Reagan Institute, George Washington University, smhs.gwu.edu/reaganinstitute/international/india/partners. Accessed April 11, 2019.

8) Nancy Angeline, Suguna Azbazhagan, A Surekha, Sushil Joseph, Pretesh R Kiran. Health impact of chennai floods 2015: Observations in a medical relief camp. International Journal of Health System and Disaster Management. Aug 2017;5(2)46-48.

9) Juyal, D, et al. “An Outbreak of Hepatitis A Virus among Children in a Flood Rescue Camp: A Post-Disaster Catastrophe.” Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology, vol. 34, no. 2, Apr. 2016, p.233., doi:10.4103/0255-0857.180354.